Amsterdam

Amsterdam

Pieter Jansz. Saenredam, Amsterdam’s town hall and Exchange Bank © Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In the seventeenth century, the Dutch Golden Age saw Amsterdam becoming a major European centre for international trade and finance. The case-study of Amsterdam as a fiscal-military hub aims to follow three major strands of inquiry in order to understand the city’s primordial role in the early modern European fiscal-military system.

Firstly, it will focus on the origins of the city and its urban network in Holland and the Low Countries as a hub where fiscal-military resources (men, money, weaponry) were being negotiated and produced. At the end of the 16th and in the early 17th century, Amsterdam and its urban network, including the nearby political and diplomatic centre of the Hague, seems indeed to bring together a series of assets already present in previous centuries in Bruges (14th-15th c.) and Antwerp (late 15th-16th c.) as late medieval arms and financial markets close to yet separate from the political centres of Lille and Mechlin. Amsterdam, however, combined these traditional assets with financial and institutional innovations as well as with a distinct urban political culture independent from strong dynastic interference, despite the presence of the hereditary stadholders of Orange. This new situation, this case-study argues, was essential to establish Amsterdam’s place within the European fiscal-military system, not to say essential to the establishment of the European fiscal-military system itself.

Secondly, using fiscal-military contracts (men, money) as well as passports (arms production) as main source material, the Amsterdam case-study will evaluate long-term trends in the city and its network’s role in supplying fiscal-military resources intended to conduct European warfare on the continent and beyond. Looking at Amsterdam as a hub allows us to go beyond state-centered approaches to the Early Modern military revolution(s) and warfare’s impact on society and state formation. Beyond a traditional urban resistance to state-building as in Tilly’s approach, cities and their merchant elites could thrive on demand for fiscal-military resources. The Dutch Republic, reaching its zenith in the 17th century before regressing as a European power after the treaty of Utrecht (1713), provides an excellent context in which to examine to what extent domestic demand drove an urban fiscal-military market also frequented by many consumers, whether they were other sovereign states or semi-sovereign companies such as the VOC and WIC (Dutch East and West Indies Companies).

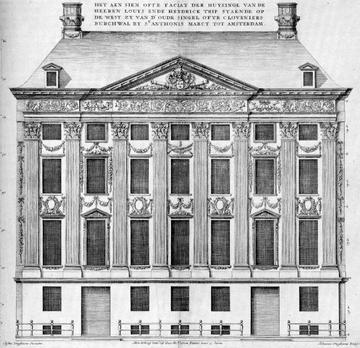

Design drawing of the Trippenhuis, built for Amsterdam-based military entrepreneurs Louis and Hendrik Trip. © Amsterdam Municipal Department for the Preservation and Restoration of Historic Buildings and Sites

Finally, the evolution of fiscal-military business in the Amsterdam hub will be compared to the general trends in the Dutch economy in the 17th and 18th centuries. From the mid-17th century onwards, the Holland economy has traditionally been presented as stagnating, if not regressing, despite recent research nuancing this view of the post-Golden Age era: did general economic developments in the Low Countries affect Amsterdam’s role as a fiscal-military hub and head of a fiscal-military Dutch network, or did the development of fiscal-military business rely on services and state investments independent from other areas of business? Hence, it will be possible to reflect on the nature of fiscal-military business in comparison to other types of business, and their respective entanglement and dependence upon each other as illustrated by illustrious entrepreneurial families such as the Trips.

Research Associate for the Amsterdam case study: Michael Depreter.